My first thought on watching the pilot for Fuller House, both a sequel and note-by-note retread of the 1980s nostalgia king sitcom Full House, was, “How did the platform that produces Bojack Horseman think this was a good idea?”

The pilot—the only episode I’ve seen, and the only episode I am likely to see any time soon—plays as an awkward mix of a self-aware “Very Brady” style parody, a winking reunion show, and an overly sincere pilot for a sincerely anachronistic sitcom. And of course, this is because it is all of those things. The entire original cast returns to reprise their roles, with one notable (and noted, in one of the only truly unpredictable moments in the pilot) exception.

Everyone gets a line or two to remind us who they are, what they did 30 years ago, and what stereotypical character traits they represent. Everyone gets a chance to mug for the camera and sneak in their catch phrases. As a side note: with an adult understanding of Bob Saget’s adult humor, it’s hard not to read the repeated references to Danny Tanner’s overweaning cleanliness as a meta-joke. The show ends with a passing-of-the-torch moment that will resonate as being truly iconic for anyone who actually remembers the original Full House pilot and leave everyone else—including people who otherwise watched the show—scratching their heads.

On the subject of predictable moments: despite having had it stuck in my head on at least 11,347 occasions in my life, I never realized before now that the first line of the theme song is “What ever happened to predictability?”

In the original series, this line was meant to be at least a bit of a wistful semi-subversion, as the show’s focus was on a non-nuclear family in a non-traditional household and all the unexpected problems and unconventional solutions they came up with. I say “wistful” and “semi”, because of course, Full House was the late-80s prime time idea of white suburban family entertainment: clean as a whistle, never quite as racy as the carefully coached hoots and hollers of the live studio audience would have us believe. (Have mercy.)

In the tacitly updated version, this same line plays a lot more straight. Whatever happened to predictability? Why, it’s right here where you left it, 29 years ago. “This baby never went out of style,” says Dave Coulier, holding up an amazing technicolor dream shirt from his character’s wardrobe. There’s a comedic beat that seems to last an eternity, by the time John Stamos replies, “That’s because it was never in style,” you will have already heard this line echoing in your head so many times that you feel like you’re stuck in a Groundhog Day loop and haven’t figured anything better to do with infinite time than watch Fuller House.

I don’t want to sound like the show is terrible from start to finish. There are a few genuine laughs early on, most of them having to do with Stephanie Tanner. The character of Kimmy Gibbler, whose defining trait is awkwardness, has the least awkward transition from decades past. She’s never had a problem making herself at home in the Tanner household before, and she still doesn’t. The character works better as a self-assured adult than as a gawky tweenager.

In many cases, the show does work as a reunion show or a nostalgic parody, so on that level it’s worth watching at least the pilot for anyone with fond if hazy memories of the original.

It’s the pilot for the actual sitcom, of which I understand some 10 or so episodes follow, that’s painful. I mentioned Bojack Horseman up above. If you’ve watched that other Netflix show (it’s kind of like Californication, “but, like, a animal version”, with the premise that the main character is a washed up star from a late 80s/early 90s sitcom, and also a horse) before sitting down to Fuller House, you’ll find it almost impossible to not have the lines “Now that’s what I call horsing around!” or “Go home, Goober!” run through your head at multiple points, and this isn’t even mentioning the danger of getting Too Many Cooks stuck in your head.

These things show us that sitcom parodies suffer from their own peculiar version of Poe’s Law. Apparently the best way to lampoon the TGIF-style shows of yesterdecade is to just follow their lead exactly, beat for beat and note for note. When you’re watching Bojack or Cooks, in the back of your head you think they’re probably exaggerating. But then you see an earnest and very conscious recreation of those same sitcom tropes and you realize, no, they worked so well because they were so completely and perfectly on the nose. And in trying to deliberately re-capture the lightning (or maybe the fluorescent lighting?) that was Full House in a bottle, Fuller House somehow does it all in an even more on-the-nose way.

So why did this show get made? And why did it get made by the “network” that brought us Bojack?

To understand Netflix’s plan, we must, as a brilliant surgeon once said, “quietly enter the realm of pure genius”. My first thought when I had actually finished watching the show was “Why was this made?” To judge by the critical ratings, that was a lot of people’s thoughts. But when we’re talking about entertainment media, that question is really, “For whom was this was made?” and if you find yourself asking that question, the answer is, “People who aren’t me.”

Compared to a traditional network, Netflix’s original programming approach seems to be all over the place. They snap up import rights, pick up discarded and discontinued shows from all over the place, make gritty dramas and savvy comedies and bizarre cartoons and licensed properties. A traditional network will cancel even a successful show if it’s attracting “the wrong demographic”, but Netflix isn’t a network at all. It’s a subscription-based distribution channel. Where a network is actually in the business of delivering eyeballs to advertisers, Netflix’s whole revenue stream is based around those eyeballs.

Thus, the point of any Netflix original production is to be the “killer app” to some group of people, the thing that gets new people to sign up. For some people, this was House of Cards. For others, it’s Orange is the New Black. Or Marvel’s [Latest]. Or another season of their canceled cult favorite.

And for some people, mostly older people who have probably never had a streaming media subscription and who otherwise likely would have been among the last holdouts? It’s going to be Fuller House.

Last spring when the show was announced, a lot of people asked questions like, “Is this going to damage the Netflix Original brand?” or “Is this going to be the death-knell for Netflix?” Well, I don’t know if Netflix has released anything like exact viewing numbers for Fuller House, but it’s apparently done well enough for them that they’ve already ordered another batch of episodes. This is not at all unusual for their original productions, and while this means we can’t exactly call the show a stand-out yet, it does seem to signal that their “brand” is fine.

There might not be a lot of Bojack or Orange fans streaming it, but have you seen how many things are under the Netflix Original banner these days? I doubt very many people, or even very many households, watches all of it.

Netflix is living in the long tail of the market, building a broad catalog of things that individually appeal to as broad a spectrum of the market as possible. This is the opposite of the traditional approach, which is to try to make everything you do appeal to the “mass market”. It gives us shows that would otherwise not exist (like Orange is the New Black, Bojack Horseman, Marvel’s Jessica Jones, or Grace and Frankie, or even Fuller House), shows that are not completely watered-down and sanitized and homogenized because when Netflix streams a series, they’re not worried about who they might turn off but who they’re going to hook in.

Simply put, Netflix doesn’t have to worry about the “18 to 35” demo with Fuller House. They already have those people’s subscriptions. Anyone who’s still worried about the future of original programming on Netflix after this trainwreck can relax.

The fact that they’re willing to make a show that does nothing for you personally indicates that they’ll continue putting out shows with no regard for pleasing everybody.

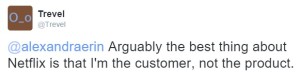

Update: After I posted this, Twitter user @Trevel had this to say, which I think just about sums up the key to Netflix’s approach:

“Arguably the best thing about Netflix is that I’m the customer, not the product.”